Tom Doherty vs The Pennine Way.

Montane Winter Spine Sprint South, the build up, the Birmingham snow drama, and 46 miles of controlled chaos!

There are races you enter to finish, and there are races you enter to find out what you’re made of.

For Tom, the Montane Winter Spine Sprint South wasn’t just “a 46 miler.” It was a full spectrum test of patience, preparation, mindset, self sufficiency, and the ability to keep moving when the world around you looks like it’s trying to push you off the hill.

This is Tom’s story, from the build up, to the travel chaos getting to Edale, to the moment he stepped into the Spine “bubble” and refused to let it break him.

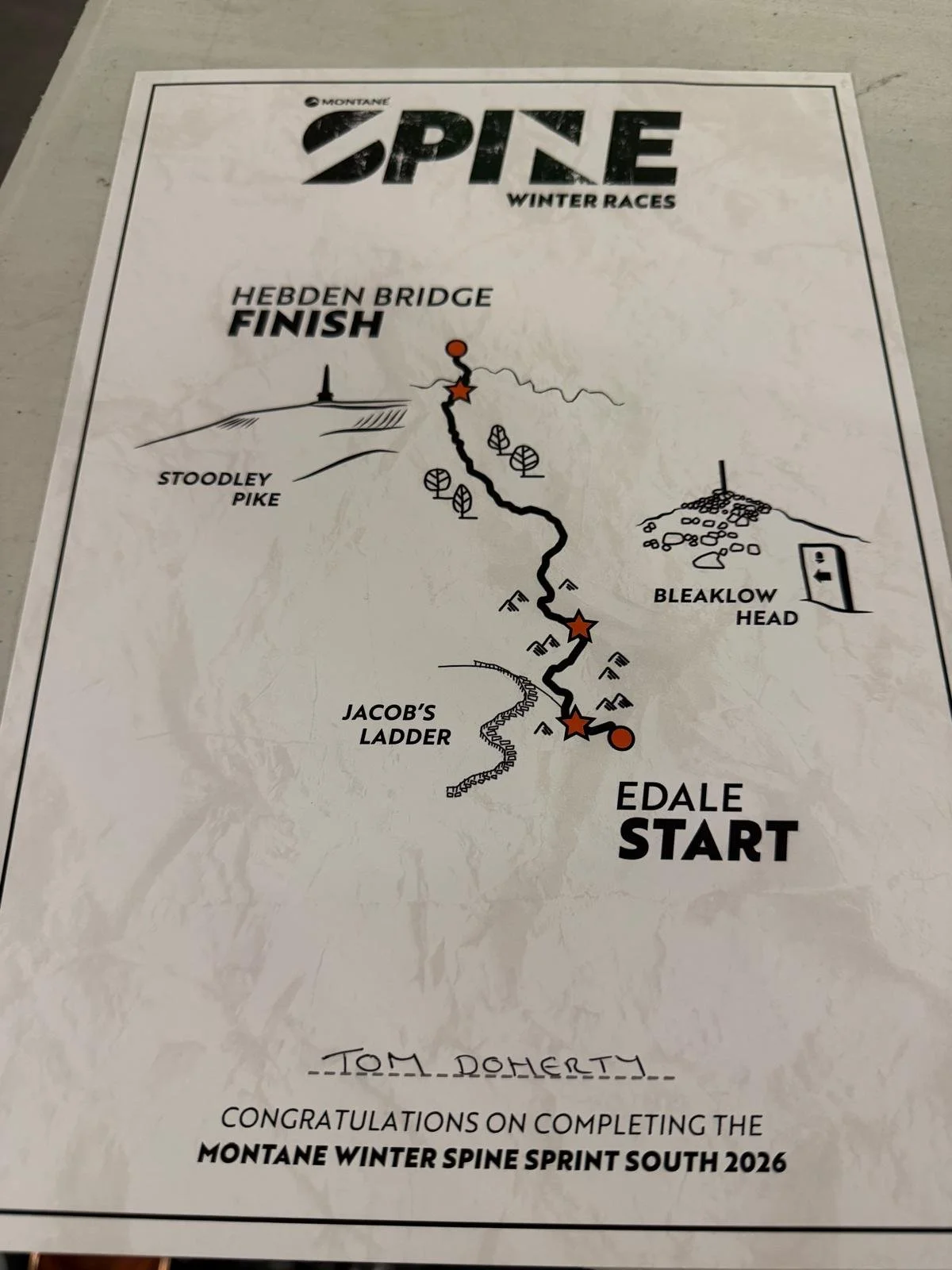

Spine Race

The race that Tom signed up for (on paper)

The Montane Winter Spine Sprint South is a non stop 46 mile race along the Pennine Way from Edale to Hebden Bridge, with an 18 hour time limit. It sounds doable when you read it. Then you remember it’s the Pennine Way, it’s technical, it’s exposed, and it demands your full attention for every step. And the weather can be brutal.

Race details (as published):

Start: Edale, Derbyshire

Scheduled start: 12:00 noon

Actual start: 13:00 (pushed back due to weather)

Distance: 46 miles

Time limit: 18 hours

Finish: Hebden Bridge

Cut off: 07:00

Total ascent: 2017m

Total descent: 2033m

The real version starts days earlier… with a taper, the flu, and the kind of snow that turns “simple logistics” into a problem solving exercise.

The build up, training, taper, and that classic pre race wobble

I’ve coached Tom for a few years now, structuring his 1:1 sessions and building the training plan that would give him the best chance of doing this properly: strong enough to handle the climbs, conditioned enough to grind for hours, and calm enough to execute. That matters on the Spine, it’s not the sort of event you “wing”.

Nothing goes smoothly, in the final week, Tom got hit with flu symptoms.

“I’d got my flu on… I couldn’t do anything. I just felt so bunged up..”

Taper week illness is a cruel little tradition in endurance sport. Sometimes it’s bad luck. Sometimes your system finally takes its chance to show you what you’ve been holding off while training load is high. The key part? Tom turned it around in time, and in a strange way, it forced the one thing lots of athletes struggle to do properly during a taper, rest.

No last minute sessions. No panic mileage. No trying to “earn confidence” in the final days. Just recovery, focus, and getting to the line.

It snowed at home.

Getting to Edale (snow, cancellations, and control)

Here’s where the story takes a proper turn, because race day doesn’t start at the start line. It starts the moment you begin the process of getting there.

The plan was originally family support: drive up, get seen off, head back. Sounds fine… until you’re the one out on the course while your wife and kids are travelling back through snow.

“There’s no way I can hit a pace on that race where I’ve got my girls in transit… I’d be terrified the entire time.”

That’s not weakness, that’s responsibility colliding with commitment. So Tom made the decision that allowed him to race without carrying fear for 46 miles, public transport, and it was brutal.

“Every other train was cancelled… by the time I arrived at the hotel in Edale, I’d been through so much stress.”

This matters because the Spine doesn’t care what your day has been like. It doesn’t refund stress. It just adds more, but Tom’s first win happened before the race even started, he got there. He ate. He slept.

“I just managed to eat… and I slept all the night.”

That’s composure. That’s maturity. That’s a man who knows the job isn’t to feel perfect, it’s to keep making the next sensible decision.

Edale: the kit check mind games

Spine kit check is its own psychological event. You look around, you see bags the size of small houses, and your brain starts whispering, You’ve forgotten something. You’re underprepared. Everyone else knows what they’re doing.

Tom travelled light, partly through necessity and partly through personality.

“I packed it so minimally… I was constantly questioning, I forgot this, I forgot that.”

And then came the reality, kit check forces you to unpack half your bag in the cold, then repack it with gloves on while everyone watches.

“The worst part wasn’t finding each item… it was the end, you’re left with a pile of shit.”

It’s small, but it’s important. Because that’s exactly how the Spine chips away at you, not one big dramatic moment, but constant admin, in constant weather, with constant consequences if you get sloppy.

Tom Pre race.

The start, spikes, slips, and Jacob’s Ladder

The race start was delayed to 13:00 to allow people to reach the start line. Then it was business time.

Tom made a deliberate decision early, don’t rush, don’t get dragged into someone else’s pace. This was about finishing, not flexing, and then the route introduced itself properly.

“The amount of people I saw just go… sliding, face planting. Brutal.”

He held his microspikes back at first because of the mixed terrain, then put them on before it got truly treacherous, and watched the cost of poor timing play out around him.

The Pennine Way in snow and Ice isn’t “hard running.” It’s foot placement, balance, braking control, and restraint.

It’s also where Tom’s conditioning showed.

“One thing I noticed was the hills… I’d pick people off on hills.”

That’s what we wanted, not the hero at mile 5, the problem solver at mile 35.

Torside, the checkpoint that looked like a war zone

Tom arrived at Torside in the dark and walked straight into what he described as a casualty site.

“People hypothermic… people with injuries… the amount of people who DNF’d there was significant.”

He felt great, but seeing that level of carnage early can play tricks on your mind. It makes you question your own reality. It makes you wonder what’s coming.

And then he heard one of the most brutally honest pieces of checkpoint wisdom you’ll ever hear from a member of mountain rescue!

“Never DNF as you enter a checkpoint, always do it on the way out.”

The Spine is mental warfare. If you walk in planning to quit, you’re already done. But if you walk in planning to reset, eat, warm up, fix something, you give yourself a chance to come back online.

Tom did exactly that.

Part of the route

The middle miles, navigation traps and the “Spine bubble”

Somewhere out on the course, the Spine does a weird thing. Your world shrinks. You stop thinking about normal life. You stop thinking about anything except:

feet

breath

temperature

food

time

the next landmark

Tom described it perfectly:

“They call it the Spine bubble… when you’re there, nothing else really matters.”

That bubble is powerful, but it can also hide mistakes, especially in snow, where paths look identical and footprints tempt you into lazy navigation.

Tom witnessed one of the most heartbreaking things you can see in a race, someone take the wrong path at the reservoir, and hit the dead end, that’s a six mile penalty for a minor mistake and could break a persons mind.

“Mentally… that would do me.”

Spine navigation isn’t just map skills. It’s decision making under fatigue. It’s humility. It’s checking, even when you think you’re right.

Coaching in real time, the cut off conversation

At one point, Tom checked in with me about the cut offs. Mountain Rescue comments had spooked him, some of them hadn’t clocked the delayed start, others were speaking as if he was “just walking,” not racing the clock. He messaged me asking how he was doing.

From a coaching perspective, that moment matters. You can’t lie to an athlete, but you also can’t hand them panic.

The guidance was simple and executable:

Keep doing what you’re doing.

Most of the climbs are behind you.

Trot the flats and downhills.

Not a pep talk. A plan.

And Tom did what good athletes do, He listened, then acted.

“When I woke up at 05:30… I thought there’s no way… and then looked at the dots on the map, he’s only a mile away… he listened.”

That’s trust built over years. That’s why 1:1 coaching works when it’s done properly.

Food fails, gel wins, and cold proof lessons

The cold doesn’t just freeze the ground. It freezes your fuelling plan. Tom carried a range of food, and most of it became useless.

“All of it… frozen solid.”

The solution on the day? Gels.

And specifically, a system that reduced faff and kept them accessible.

“A gel pouch is a game changer… I can’t rave about them enough.”

But the bigger lesson is one every athlete should learn before their next cold ultra:

If it freezes, it fails.

If it’s fiddly, you won’t use it.

If it isn’t accessible, it doesn’t exist.

Finishers Certificate

The final stretch, picking people off and refusing to bargain

Towards the end, Tom did what strong endurance athletes often do, he started moving through the field.

“At the end, I was just picking people off.”

Even then, he didn’t give himself permission to believe it until it was undeniable. The earlier doubt lingered. He wasn’t taking chances.

He reached Stoodley Pike, a landmark that, for anyone who knows the area, hits like a signal flare, you’re nearly home.

“I know this place now… once I’m there, I’m home and dry.”

But even then, the Spine demanded respect: a slip after taking spikes off too early, a reminder that you don’t get to relax until the job is finished.

The finish, relief, soup, and that weird post race high

Tom finished, and then the fatigue hit, not because he was broken, but because the mind finally allowed it.

“When you finish… your mind goes ‘relax now’. It’s over.”

Then came the part anyone who’s completed something properly terrifying understands, he got home… and felt energised.

“I got home and I was completely energised.”

That’s the aftershock of competence. The body’s tired, but the brain is lit up because you proved something to yourself.

Tom Finished

Biggest challenge, biggest lessons, and what comes next.

The biggest challenge, snow, and the energy cost of moving through it for hour after hour. Footprints, soft ground, poles sinking, constant stabilising, constant concentration.

My three biggest lessons:

Doing a Recce matters. Not just for navigation, but for pacing, landmarks, and reducing fear of the unknown.

Food needs a cold proof strategy. If it freezes, it’s not fuel.

Kit tweaks are performance. Gloves need retention, goggles need to be accessible, and durability beats “lightweight” when the conditions bite.

Maybe the biggest takeaway of all:

“There was no way I was not gonna finish that… medal or no medal.”

That mentality is what the Spine demands. Not bravado, just commitment. Now Tom’s looking at the next step with a different kind of confidence:

“The idea of the 108-mile Challenger… now, I’ve got the confidence I can go and do that one.”

And that’s the real win. The Sprint wasn’t the end. It was the start of another adventure.

Coach’s note, why Tom got this done!

Tom didn’t finish because everything went smoothly.

He finished because he solved problems in real time.

adjusted the travel plan to protect his headspace

controlled effort instead of chasing ego

managed fear without feeding it

used the climbs as his advantage

stayed calm in a checkpoint full of DNFs

and followed a simple plan when the clock got loud

That’s what we trained for.

Not “fitness” but Capability.